Author: Stacie Sanchez

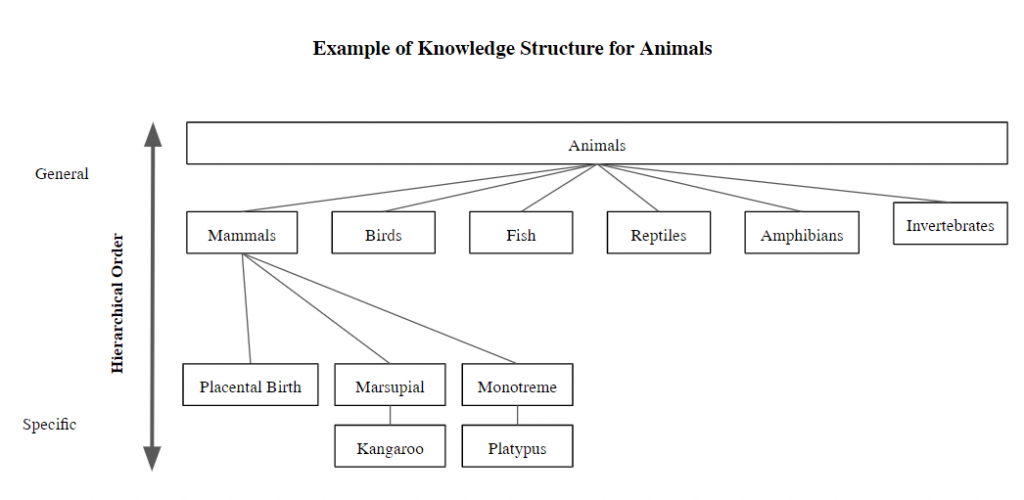

Today we’re going to go over associative learning and knowledge structures. Associative Learning is the process by which thoughts, ideas, or concepts, can be associated with one another. Psychologists postulate that we internally organize knowledge by these associations into hierarchical, Knowledge Structures. Let’s break that down. Knowledge structures are simply how we organize knowledge about everyday life. Psychologists often use schemas, mental models, scripts, etc. to explain how we organize information, but they all refer to some knowledge structure that helps us make sense of our world. Much as birds of a feather flock together, associated thoughts stick together. Everyday knowledge is organized around concepts or groups of concepts called nodes. These nodes are linked to associated concepts or ideas. Concepts that are more associated with each other are likely to cluster closely together than concepts that are less associated. These associations have a pecking order, or hierarchical order, with overarching concepts sitting at the top and more specific concepts sitting lower underneath these general categories. Let’s look at a knowledge structure example for animals. Jumping back to early elementary biology, we may internally organize animals based on what animal class we associate them with: mammals, birds, fish,reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. Notice that these categories are very general. More specific groups live underneath these categories. For example, when considering how mammals give birth, we could break mammals into three associative groups: mammals that give placental birth, mammals that lay eggs (monotremes), and mammals that give birth to not fully formed young (marsupials). Under these groups, there may be even more information, such as the types of animals that fall under marsupials. See below picture for a visual representation.

How does this information help in the real world? We live in a dynamic world. In everyday interactions, we are bombarded with a plethora of information that needs to be assessed quickly with often limited cognitive resources. Knowledge structures help support these cognitive resources by giving us a blueprint or internal schematic by which we can begin to reason and understand our situation or environment. When we engage a concept, activation spreads to nearby, closely associated nodes, known as Spreading Activation. This activation helps bring useful information to the forefront to help assess the current situation.

How does this relate to studying? To help build associations, we can use a studying technique known as mnemonics. Mnemonics is a studying technique that uses associations to help remember a series of concepts. Mnemonics can be words or phrases. When we create mnemonics, what we are doing is creating an associative link in our knowledge structure between the word/phrase and a series of information. When we call up the mnemonic on an exam, we help activate spreading activation to bring concepts we have associated with the mnemonic to the forefront. For example, a student studying our solar system may use the mnemonic “My very educated mother just served us noodles” to remember the order of the planets from the sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupitar, Saturn Uranus, and Neptune. This however is only as useful as the strength of association between the mnemonic and the information trying to be associated.

For help developing stronger associations see Active Recall and Elaborative Rehearsal.